Opening — Why This Matters Now

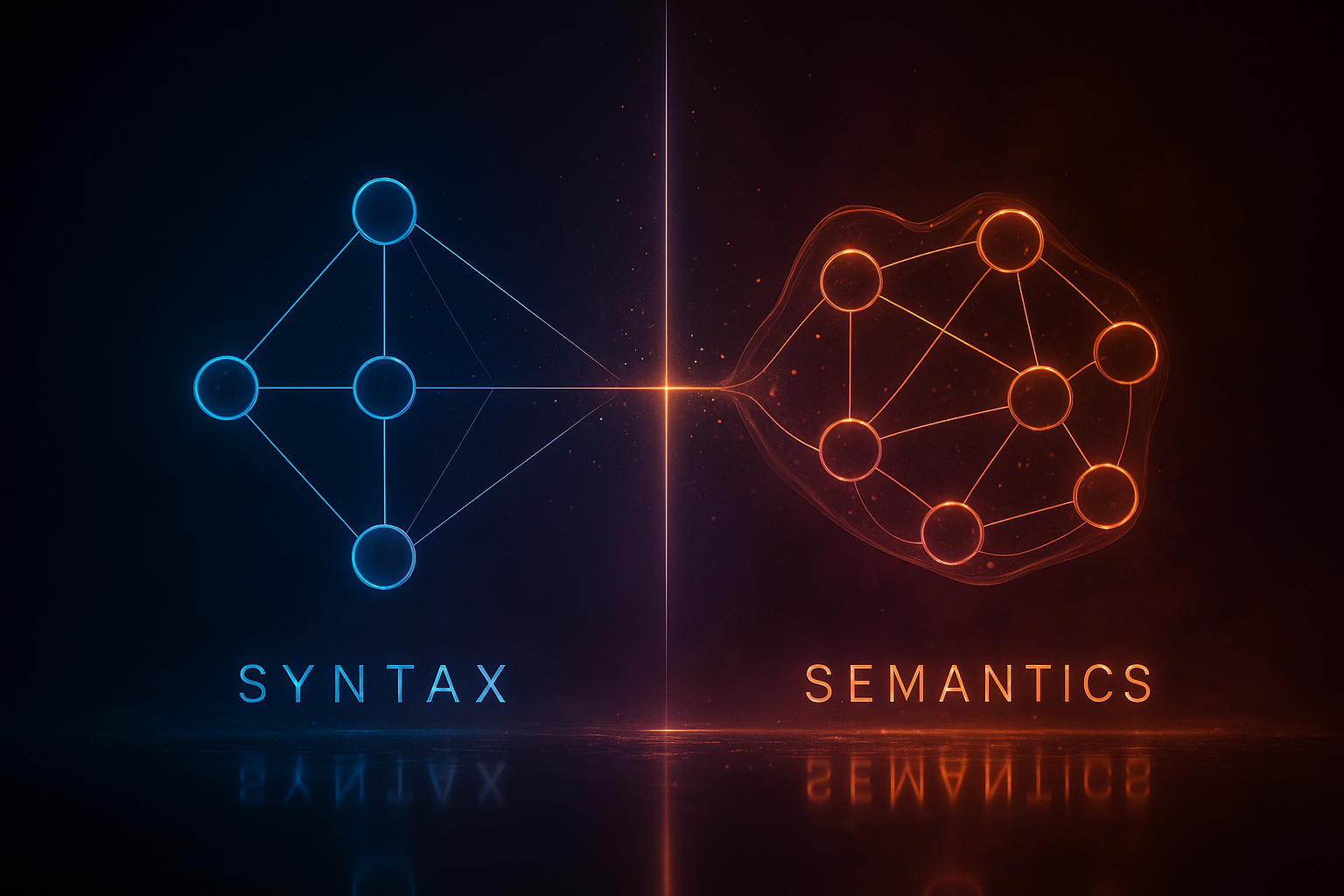

Probabilistic graphical models (PGMs) have long powered everything from supply‑chain optimisations to fraud detection. But as modern AI systems become more modular—and more opaque—the industry is rediscovering an inconvenient truth: our tools for representing uncertainty remain tangled in their own semantics. The paper at hand proposes a decisive shift. Instead of treating graphs and probability distributions as inseparable twins, it reframes them through categorical semantics, splitting syntax from semantics with surgical precision.

Why does this matter now? Because as AI deployments scale, organisations need tools that support interpretability, composability, and mathematical guarantees. Category theory—yes, the discipline many engineers fear—turns out to offer unusually sharp instruments for reasoning about structure without prematurely committing to meaning.

Background — Context and Prior Art

Traditional PGMs come in two flavours:

- Bayesian networks (DAGs) for causal reasoning.

- Markov networks (undirected graphs) for symmetric correlations.

These two worlds have always been bridged by two technical operations:

- Moralisation: converting a Bayesian network into an undirected graph.

- Triangulation: converting a Markov network back into a DAG, usually to enable exact inference.

Both are essential for inference algorithms like variable elimination and junction tree construction. But they also mix syntax (graph structure) with semantics (probabilities), often in ways that obscure what operations actually rely on numerical assumptions.

Category theory has been creeping into probabilistic modelling for years, offering strong compositional tools. Prior work already characterised Bayesian networks as functors from a string‑diagrammatic syntax (CDSyn_G) into a semantic category like FinStoch (stochastic matrices). The current paper extends this perspective to Markov networks through hypergraph categories, giving both formalisms a shared algebraic backbone.

Analysis — What the Paper Actually Does

The authors rebuild PGMs around a clean syntactic–semantic split:

1. Syntax becomes the free categorical structure generated by a graph.

- For Bayesian networks: CD‑categories representing copy/delete behaviour.

- For Markov networks: hypergraph categories representing Frobenius algebra structure.

2. Semantics becomes a functor from that syntax into a category of matrices or stochastic maps.

This yields:

- A bijection between Bayesian networks and CD‑functors.

- A parallel bijection between Markov networks and hypergraph functors.

- A purely algebraic description of moralisation and triangulation as functor precomposition.

Most importantly, triangulation is factored into two functors:

Tr_C(syntactic triangulation): a purely combinatorial step.VE(semantic triangulation): a semantic check resembling variable elimination.

This exposes which parts of inference are purely structural—and which embed actual probabilistic computation.

Findings — Results and Visual Frameworks

The paper provides a modular decomposition of PGM transformations, summarised by this commutative diagram:

BN ← Tr ← MN → Tr_C → CN ↑ ↓ Mor VE ↑ ↓ BN ← Tr∘Mor ← MN → Mor_C → CN

Where:

- BN: Bayesian networks

- MN: Markov networks

- CN: chordal networks (structural intermediary)

All operations reduce to algebraic manipulations of syntax and semantic functors.

Table — Distinguishing Syntax vs Semantics

| Operation | Purely Syntactic? | Requires Probabilities? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moralisation | Yes | No | Adds edges among parents; functorial via precomposition. |

Triangulation (Tr_C) |

Yes | No | Builds chordal structures. |

Variable Elimination (VE) |

No | Yes | Requires normalisation; acts as semantic triangulation. |

| Junction Tree Message Passing | No | Yes | Cannot be fully described without division operations. |

Example Insight

The four‑student example in the paper demonstrates why undirected factor graphs sometimes capture symmetry that DAGs cannot. The string‑diagram view makes each clique’s contribution explicit—an advantage for auditing or regulatory settings where clarity of dependencies is mandatory.

Implications — Why This Matters for Industry and AI Governance

This categorical treatment isn’t just academic elegance. It hints at practical consequences:

1. Modular verification pipelines

By isolating syntactic transformations, organisations can validate structural assumptions before touching probabilities—critical for safety‑critical AI deployments.

2. Interchangeable inference backends

A unified syntax means one can swap semantic interpretations (e.g., stochastic, Gaussian, measure‑theoretic) without rewriting entire models.

3. Better auditing and explainability

Composable, diagrammatic semantics makes hidden assumptions visible. Regulators love this.

4. Foundations for automated model repair

Since independence properties are captured algebraically, future tools could automatically:

- identify violations,

- repair missing edges,

- or propose causal structures supported by data.

5. Potential bridges to agentic AI architectures

Future multi‑agent systems may rely on graph‑structured uncertainty propagation. A categorical framework offers a stable backbone for these architectures—more reliable than ad‑hoc DAG stitching.

Conclusion — Steadier Foundations for Uncertain Worlds

This paper reframes probabilistic graphical models through categorical semantics, transforming moralisation, triangulation, and variable elimination into elegantly composable functors. It clarifies what is structural, what is probabilistic, and what is merely conventional wisdom. For an industry struggling with interpretability and modularity, this algebraic backbone might prove more valuable than yet another neural architecture.

Cognaptus: Automate the Present, Incubate the Future.