Opening — Why this matters now

Explainability in AI has become an uncomfortable paradox. The more powerful our models become, the less we understand them—and the higher the stakes when they fail. Regulators demand clarity; users expect trust; enterprises want control. Yet most explanations today still amount to colourful heatmaps, vague saliency maps, or hand‑waving feature attributions.

The paper A Framework for Causal Concept-based Model Explanationsfileciteturn0file0 enters this landscape with a refreshingly serious proposition: What if explanations were actually causal, actually semantic, and actually faithful to the model’s internal reasoning, rather than decorative post‑hoc approximations?

In other words: what if we stopped treating explanations as magic tricks and started treating them as engineering artefacts?

Background — Context and prior art

Traditional post-hoc XAI tools—LIME, SHAP, Grad-CAM—follow a single pattern: describe correlations in a model’s behaviour and hope the human interprets them causally. That hope is rarely warranted. When the input space is high‑dimensional (pixels, tokens), these tools over‑index on local gradients and mislead users into thinking the model reasons in the same categories humans use.

Causal XAI attempts to step above this mess by introducing explicit causal structure. Meanwhile, concept-based XAI (C-XAI) argues that explanations should use human-understandable units—“glasses,” “smiling,” “big nose”—not raw pixels.

This paper merges both philosophies.

It argues that:

- Explanations should use concepts, not features.

- Explanations should model causal mechanisms, not correlations.

- Explanations should quantify counterfactual sufficiency, not proximity in feature space.

This pushes XAI from diagnostic heuristics toward something closer to scientific reasoning.

Analysis — What the paper actually does

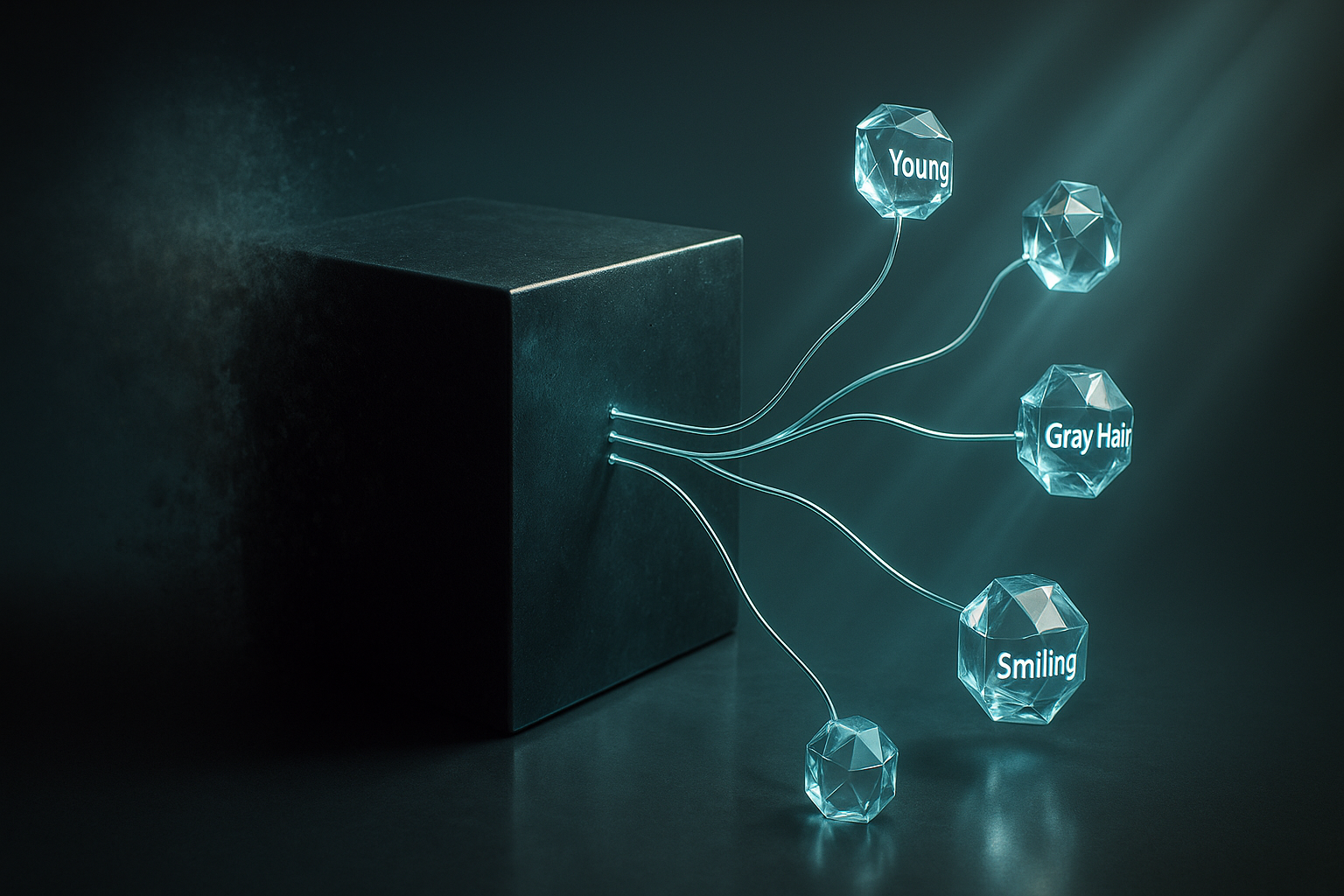

The authors articulate a full-stack causal explanation system with three key components:

1. A vocabulary of high‑level concepts (z)

These are human-interpretable units—e.g., “Young,” “Gray Hair,” “Pointy Nose.” They form the language of explanation.

2. A causal model (M) over those concepts

Represented as a Structural Causal Model (SCM), allowing true counterfactual queries: If this concept changed, what would happen to the model’s prediction?

3. A deterministic mapping (α) from concepts → data features

This bridges the semantic space (concepts) and the model’s visual input space. In the demo, the authors implement this via StarGAN for image-to-image translation.

Together, these components produce causal explanations describing how changes in concepts would change the model’s predictions.

Key innovation: Probability of Sufficiency (PS)

Instead of gradients or feature weights, the framework uses probability of sufficiency—a Pearlian causal metric—to quantify how strongly an intervention on a concept can flip a model’s output.

Mathematically, it evaluates: $$ P(\hat y_{do(z = z’)} = y’ \mid x, \hat y) $$ This is not correlation. It is not regression. It is a counterfactual causal query.

Local vs. Global explanations

- Local: Explain a specific instance by simulating counterfactual changes.

- Global: Summarise how concept changes affect predictions across a population.

Both are grounded in the same causal machinery.

Distinguishing feature: Faithfulness with an explicit causal context

You cannot interpret these explanations without accepting the assumptions behind the causal model M. The authors are explicit about this—almost to a fault—which is exactly what responsible XAI requires.

Findings — Results with visualization

Using CelebA face classifiers (“Young?” and “Attractive?” tasks), the authors show how the causal framework behaves differently from typical attribution tools.

Example: Explaining age predictions

A model might classify a face as “young.” The causal framework evaluates:

- What if we change Gray Hair?

- What if we intervene on Young directly (and propagate causal effects such as wrinkles, glasses probability, etc.)?

Surprisingly:

- Gray Hair had much stronger causal influence than Glasses.

- Intervening on Young itself (propagating its downstream causal effects) almost always flips the prediction.

Example: Explaining attractiveness predictions

Interventions reveal gender-specific causal differences:

| Concept Intervention | Effect on Prediction (Female) | Effect on Prediction (Male) |

|---|---|---|

| Remove Big Nose | Very high causal sufficiency | Moderate effect |

| Add Pointy Nose | Strong increase | Strong increase |

| Arched Eyebrows ↑ | Small increase | Very small |

| Smiling ↑ | Moderate | Moderate |

The contrast with TCAV and Grad-CAM is stark: causal effects diverge significantly from gradient-based attributions.

Why this matters for practitioners

This framework doesn’t just say “the model looks here.” It says:

“If this concept changed, the model would (or would not) change its decision—here is the quantified causal probability.”

That is operationally useful.

Implications — What this means for business and AI governance

1. XAI is moving from decoration to diagnosis

Saliency maps look scientific but often aren’t. A causal model that generates counterfactuals provides a higher standard of evidence.

2. Better auditing for bias and robustness

Global sufficiency scores reveal population‑level vulnerabilities:

- whether age correlates improperly with “attractiveness”

- whether makeup disproportionately affects predictions

- whether gender mediates unintended causal links

This enables targeted dataset and model fixes.

3. Actionable insights for high‑stakes domains

Causal concept explanations are especially relevant for:

- credit decisioning

- medical diagnosis

- hiring evaluation

- insurance underwriting

These domains demand counterfactual reasoning (“If X had been different, would the outcome change?”). This framework provides it natively.

4. But only if assumptions are made explicit

The paper is refreshingly honest: the causal model is only as good as its assumptions. Bad causal graphs produce misleading explanations.

For enterprises, this implies:

- Explanation systems need governance.

- Causal models require domain experts.

- The explanation context must be aligned with deployment context.

Conclusion — The road ahead

This paper is not a turnkey XAI system—it is a blueprint. But it is a blueprint that pushes the field in the right direction: toward causal, concept-level, model-faithful explanations instead of ornamental justifications.

For any organisation navigating AI transparency, the framework offers a simple but profound message:

If you want explanations that behave like reasoning, build them using causal reasoning.

The future of trustworthy AI will belong to systems that can explain not just what they predict, but why—in terms humans actually understand.

Cognaptus: Automate the Present, Incubate the Future.